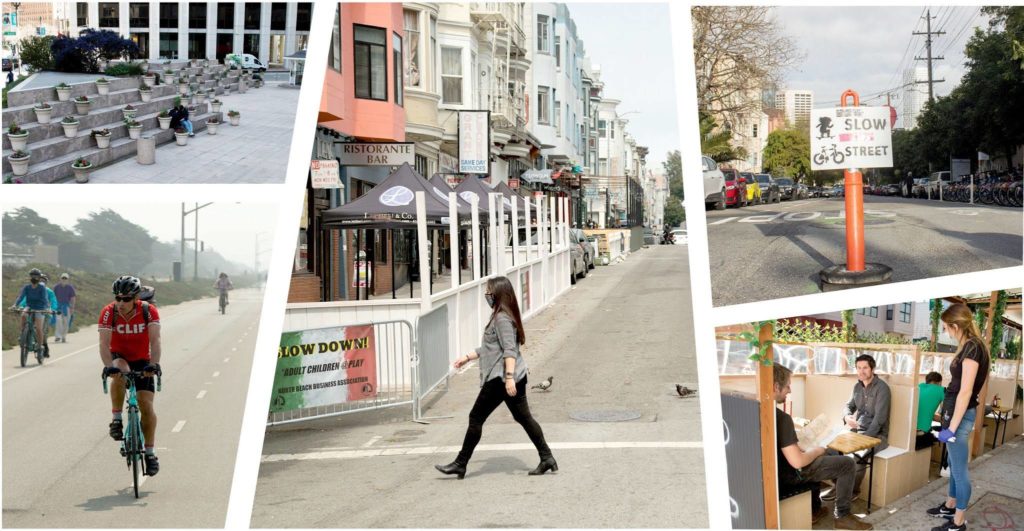

Walk down Page Street, which is closed to thru-traffic, and you might encounter a front stoop instrumental concert, kids on training wheels or sidewalk chalk art. Head to North Beach and you’ll pass dozens of elaborate outdoor dining platforms. Or, check out Valencia Street, where merchants have created a vehicle-free destination to shop, dine and find entertainment.

These creative uses of public space were hard to find before the pandemic. Now, some can’t imagine a San Francisco without them.

Over the last 12 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has altered life for San Franciscans, but it’s also fundamentally transformed the face of The City itself. Our year-long battle with the coronavirus has forced residents, businesses and city agencies to adapt in order to survive.

Changes that might have once taken years have been pushed through swiftly, as The City converts streets into pedestrian promenades, parking spaces into outdoor dining venues and neighborhood commercial corridors into anchors of community life.

But as more people are vaccinated and signs of pre-pandemic life creep back, San Francisco faces another daunting task: forging a path ahead after a year of crisis.

Among the questions leaders must grapple with are: which parts of this new face of San Francisco should be made permanent? And how do we make sure benefits are bestowed upon many rather than few?

A section of Valencia Street was closed to vehicle traffic to allow for dining and open space in July 2020. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)

Redefining neighborhoods

Almost overnight, as shelter-in-place orders took effect, neighborhoods that were previously the bookends of daily life for many San Franciscans became the primary place where people lived, worked and played.

As a result, the idea that thoughtful use of public space and easy access to green space, bike-friendly streets and other amenities such as playgrounds should be considered critical infrastructure started to take hold.

“San Franciscans have always valued their neighborhoods, but our neighborhoods are becoming increasingly important as we spend more of our time at home and need to access services and retail and institutions in our neighborhoods,” Planning Department Director Rich Hillis said, adding that key to that mission will be building additional housing, affordable and market-rate, in areas across The City.

In response to the realization that neighborhoods need to be both functional and fun, The City created Slow Streets, which closes select residential streets to thru-traffic, and Shared Spaces, which allows businesses to use parking spaces and sidewalks for commercial operation.

“The pandemic has resulted in a once-in-a-generation level of despair,” said San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Director Jeffrey Tumlin. “We’re using the public right of way to foster a sense of togetherness, public joy and hope.”

Creative use of public space also can maximize public benefit in a time of severely limited resources.

The Great Highway was closed to vehicles in 2020. The change has proved popular with pedestrians and cyclists, but neighbors have complained of traffic impacts. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)

The Slow Streets network has helped bridge mobility gaps left behind by 40 percent service cuts and the suspension of Muni Metro. Today, it’s possible to ride a bike from Ocean Beach to the Embarcadero on a virtually car-free route.

“It’s not just about the parks, but how do we create those spaces between the parks to also be part of that dynamic,” Jeff Cretan, communications director for Mayor London Breed, said of the push to experiment with ways to bring people onto the streets.

Relatedly, changes to curb management have helped reinvigorate commercial corridors by prioritizing businesses, outdoor dining and social engagement.

Shared Spaces is a prime example of turning a public good into a vehicle for economic recovery. As of March 1, The City had approved 2,117 Shared Spaces permits, with the goal of keeping those businesses open and workers employed, but also to creative avenues for recreation and community-building in an extended period of isolation.

“It’s our task to manage the public right of way to foster the greatest possible good,” Tumlin said. “So the question becomes whether the public good is best fostered by renting that curb space to store a vehicle or for people to be able to enjoy a meal?”

San Francisco’s top officials have supported bold uses of public space during the pandemic, with the mayor and the Board of Supervisors calling for elements of Shared Spaces to be made permanent.

“She has seen what it means for our neighborhoods, our residents and our businesses to bring everybody out on the streets so they can be around one another, even in a time as challenging as the pandemic,” Cretan said.

The future of downtown

But does this attention on neighborhoods forecast an end to downtown?

Despite a national narrative painting The City as being in a tailspin, local officials say not so fast.

It’s true that San Francisco has been hit harder by the pandemic than many other cities, based on data on small business closures, outmigration and unemployment.

Chief Economist Ted Egan attributes this to several factors, among them the sizable influence of the tech industry, which has swelled to account for roughly 18 percent of all private sector jobs in The City. That’s up from about 6 percent in 2009.

Now, with massive employers such as Salesforce and Twitter adopting hybrid work-from-home or optional remote models, many employees who once spent money at downtown merchants, lunch spots and transit stations have taken their dollars elsewhere.

Vehicle traffic was curtailed under the Slow Streets program. (Jordi Molina/Special to the S.F. Examiner)

Sales taxes reflect this shift, as these revenues dropped more in San Francisco’s downtown corridor during last summer’s surge than compared to elsewhere in The City, according to Egan.

There’s also the hit to San Francisco’s $10 billion business travel and tourism industry, which generated $771 million in taxes and fees in 2018. Nearly 20 percent of the industry’s worth could be tied solely to events at Moscone Center before the pandemic rendered conventions a relic of a bygone past.

Still, officials remain confident in the eventual comeback of downtown, calling the current moment just another iteration of The City’s storied boom-and-bust history.

And while they emphasize it’s unlikely to look exactly the same as it did before the pandemic, officials say basic economic principles of supply and demand will bring tenants to currently vacant commercial buildings.

The real question is whether the new occupants will fundamentally alter the structure of The City’s economy.

“That’s what I’m going to be paying attention to,” Egan said.

A pedestrian crosses Shotwell Street, a Slow Street in the Mission District on Monday, Feb. 1, 2021. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)

A new way of doing business

With 80,371 households leaving San Francisco over just eight pandemic months in 2020, up 77 percent from the year prior according to U.S. Postal Service change-of-address requests, and the realization from large employers that they can decrease costs, boost employee happiness and attract a wider array of talent with a hybrid-remote policy, Egan expects economic recovery will be slow, but not stagnant.

Though more sluggish than hoped for at the pandemic’s outset, recovery will be bolstered by enhanced efficiency at the local level, calling on lessons learned from the accelerated pace of change that has characterized The City’s response to COVID-19.

Changes to public space, mobility patterns and planning processes that would have taken years to execute have been made in a fraction of the time during the pandemic.

“Too often we get in our own way from delivering projects, helping businesses open or building housing,” Cretan said. “So often The City’s bureaucracy and processes get in the way.”

Shared Spaces, for example, might have taken years to pull off before the pandemic, according to Hillis, but The City made it happen in a matter of weeks.

Less visible changes have also been made more expeditiously, including moving permit processing online, rolling out transit-only lanes and bikeways, using headways to schedule Muni and creating a virtual public comment process that allows more diverse participation.

Mike Porcaro lifts weights outside MX3 Fitness along Market Street in the Castro on Wednesday, July 29, 2020. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)

“What we’re finding is we can have much more effective and democratic public engagement by actually experimenting in the streets with temporary measures, and using those as part of our evaluation process,” Tumlin said. “It is far faster, far cheaper, far more democratic and it builds real trust with San Franciscans.”

Proposition H, passed by San Francisco voters in November, streamlined the business permitting process so owners can get their shops operational quicker, and it gave merchants more options for using their space; Sen. Scott Wiener introduced legislation to modernize statewide alcohol laws to provide restaurants, bars and music venues more flexibility in how and where they serve booze; and Breed has supported legislation that would make it harder for individuals to use the appeals process to delay temporary projects or those related to health and safety.

Equity concerns

The pandemic has made it glaringly obvious that inequity runs deep throughout The City.

Areas with high concentrations of essential workers, lower income earners and people of color have endured higher rates of COVID-19. They’ve also been last in line to enjoy some of the benefits of San Francisco’s changing landscape, despite needing support the most.

“It is imperative to have accessible, equitable, well maintained and cared for public spaces for economic opportunity, social connection and public health reasons,” said Michelle Huttenhoff, planning policy director at the regional think tank SPUR. “Everybody needs to have access to such spaces within a 10-minute walk or bike ride from where they live.”

But that’s never been the case for people living in parts of the Tenderloin, SoMa and Bayview-Hunters Point; meanwhile, advocates say transformative COVID-19 uses of public space are off limits to the homeless or people experiencing housing instability.

Nathan Carda, owner of Nate’s Barbershop, cuts the hair of friend and client Anthony Killsright outside his Broad Street shop in Oceanview after barbers and hair salons were allowed to reopen for service outdoors on Tuesday, Sept. 1, 2020. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)

“I love walking down the street and seeing people in parklets, at restaurants, trying to socialize in the best way they can,” said Shanti Singh from Tenants Together. “But do people who can’t afford rent and aren’t dining out, or don’t have a home at all, have that same access to COVID public space? Not really.”

Under Slow Streets, it took months for the Tenderloin to receive traffic calming treatments. Officials cited the outdated infrastructure, hilly roads and stop lights as reasons they couldn’t be implemented before finally closing some blocks.

While the SFMTA is conducting community outreach for potential Slow Streets in Bayview-Hunters Point, SoMa and Visitacion Valley, among others, what good is a road closed to vehicles if many residents don’t feel safe walking or riding their streets, or are unable to connect to transit networks?

Shared Spaces is even more fraught, raising concerns around sidewalk accessibility for individuals with limited mobility, affordability of outdoor operations and construction of potentially hostile dining platforms that degrade the dignity of people who are homeless.

Tenderloin merchants worked together to close part of Larkin Street to allow for outdoor dining on Friday, Sept. 25, 2020. City officials were slow to implement Slow Streets and other programs in the Tenderloin, citing issuse including the number of stop lights in the densely populated neighborhood. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)

Businesses with Shared Spaces permits say they’ve been a lifeline, but merchants of color and in lower income neighborhoods without foot traffic, spending and strong merchant associations report struggling to afford the cost of building a platform, manage new technology and navigate the permit process.

Additionally, it’s been hard to tap into The City’s aid. Some business owners connected to the Latino Task Force, for example, say they’ve been unable to access much of the nearly $90 million in loans and grants from the Mayor’s Office designed specifically to support small businesses, especially those in historically underserved neighborhoods.

Physical environments of the neighborhoods also present challenges, as business owners must deal with overcrowded sidewalks or roads with potholes, for example.

Any permanent rethinking of public space in San Francisco must identify comprehensive remedies for the problems that pandemic-era initiatives have exposed. Officials say legislative proposals will aim to do so.

“These are deep systemic problems that we have to continue to work on,” Cretan said of the path to permanence for some programs. “There’s so much work that needs to go into this, but the pandemic has laid bare those inequities and shows the work we have to do.”

Grant Place Restaurant and Washington Bakery and Restaurant in Chinatown drew a handful of diners on Friday, July 24, 2020. Many Chinatown businesss owners have struggled to navigate the permit process for Shared Spaces and other city programs. (Kevin N. Hume/S.F. Examiner)